One Chance

Courtesy of Say it With Games

In Dean Moynihan's One Chance, you have one chance to save the world. The player takes the role of Dr. John Pilgrim, lead scientist on the team that successfully cured cancer. The first day he is showed with praise and admiration...but after a screen indicates that in one week, every human cell on earth will die. He must choose between working and celebrating before going home. The second day will reveal the truth, that the "cure" not only kills diseased cells, but all living cells. Suddenly the simple, desaturated graphics and somber music seem more fitting. He goes to work and one of his coworkers jumps off of the building, knowing they've doomed mankind. Each day ticks a long with more choices. Do you keep working or do you stay with your family? Do you stay true to yourself or go mad? Do you give up or keep going? And every day you step outside to see the plants dying, and the crowds in the street going from normal, to riotous, to empty. And you truly do only have once chance as restarting or reloading the game will simply take you back to whichever ending you got.

Everything technical about the game is extremely simple; the art design is in simple pixels, the only actions are walking and pressing the spacebar to interact, and all of the dialog is very short with no character speaking more than two lines at a time. All of this is to bring focus onto the complexity of the game's theme and the weight of the player's decisions. It poses some very heavy and very real questions and, although a situation like the one the game depicts is highly unlikely, man people will have to ask themselves similar questions. How important are your family and relationships? At what point will you abandon your morals? How much will you sacrifice for the greater good?

But the most important technical feature is the inability to reload and try again. As Moynihan says:

"To me, choices within games often feel a little arbitrary. The fact that players can go back and undo that choice on a whim takes away from making the choice in the first place. I’ve become used to thinking “Right, I’ll take up G-man’s offer now. But when I reload my save, I won’t”. Which isn’t really making a choice at all. It just depends which ending I want to see first. Obviously, for some games this isn’t the case; exploring the choices and consequences is half the fun. But they’re not real consequences, are they?" Moynihan, Dean. (2010). One Chance, 1470 Words: Interview with Rock, Paper, Shotgun.

He references the Half Life series and it isn't the only choice based game out there. Famously games like the Mass Effect Trilogy by Bioware are known for posing heavy moral choices on their players. In fact the choices you make in that game are even more massive in scale and affect the fate of the entire galaxy. Your actions determine whether your friends live or die, whether you cure diseases or keep them active for political gain, or even whether you let entire sentient species go extinct. But in games of that scale a save/load system is absolutely necessary. One chance is short and can be completed in a couple minutes while each Mass Effect game is potentially dozens of hours long. This gives the player the ability to "save spam" and keep trying different options until they find the result they prefer. And, when this is the case, to how much of an extent is it a choice and consequence game? That is just the thing about real life decisions is that we have no way of knowing the potential impact of our choices. We can guess and predict and weigh our options, but what's done is always done.

Courtesy of GameCrate

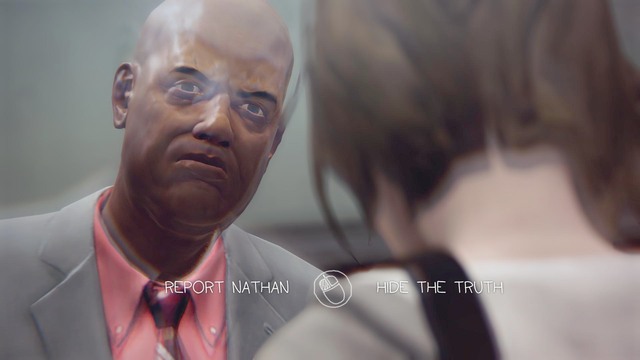

Another game with a different take on permanent choices is Life is Strange where the player takes on the role of a teenage girl suddenly imbued with the power of time travel. With the many opportunities the player has to wind back and say something different or go with another action, you would think the choices here might not have much weight and you can continually undo what you would through save spamming through a built in mechanic. However, the game is five episodes long so you may not see the outcome of one action until three episodes later or know how influential that choice will be. Not only that but there is a point in the game where your ability to time travel no longer works, and unfortunately it comes right as your friend, who has been bullied relentlessly, is about to jump from the school's roof. And you have, that's right, one chance to save her by picking the right dialog options to talk her down. Even though the choices in the game are fairly permanent, this one in particular is extremely jarring as you cannot pick your options so lightly anymore.

Courtesy of GamePressure

But there is another aspect here besides choice and consequence and that is the simple style to deliver a complex message or loaded questions. Art, much of the time, exists to make us think. Artists often seek to put things into a different perspective then we see day to day, allowing viewers to be critical of the world and themselves. Digital media, often immersive and interactive, can drive this reflection even further as they prompt viewers to think, 'what if this were me? What would I do?" The world's issues are often exceeding complicated, and how can they not be when we live in a world of billions of different minds? But simpler styles can strip down issues to their barest parts so people can understand their roots.

In One Chance, the player is never given much information. What John's family life is like, what he is actually working on when he's working, what kind of person he was up until the story is all unknown. That fact leaves fewer variables on the table when the player makes their decisions. It allows for more freedom of thought, more introspection, and more ability for the player to insert themselves. This is a direct contrast to Mass Effect which has long, rich lore and complicated politics, where decisions are made by a customized, but much more specific character.

Moynihan uses this style of pixel graphics and "walking simulator" gameplay in all of his games. Another is SOPA/PIPA, named in reference to internet censorship laws proposed in 2012. The game was created during the internet blackout on January 18th as a protest. The game is only a minute or two long if the player keeps walking but within that time they are welcomed into a new world in which you enter a designated free speech zone, given your free speech card, shown a wall of black censor-bar art, and are told over and over again that you are now free, despite the barbed wire wrapped wall you are enclosed in.

Courtesy of the artist.

In this way Moynihan simulates an experience that is quite deep, profound, and unnerving in only a few minutes with simple greyscale pixels. Games are rarely made in protest, mostly due to the time and resources they take to make. Simple graphics make this possible. But they also aid in making everything about the game stand out so there is nothing there to be missed, glossed over, or seen as irrelevant. That's why many art games adapt such a style and it mimics the simplicity and transparent structure of many other forms of digital art.

Games are designed to craft experiences. Art is made (often) to ask questions and start discussions. This outlines the unique place art games have between the two. Utilizing this medium, Moynihan is able to both insert the player into a dark, terrible world and ask, "what if this happened?" "What if this were you?" It challenges other games where choices are often temporary and made frivolously by forcing the player to think through things deeply, games where action and polished graphics take precedent over the story by stripping his down to the core message and narrative so that the player isn't just interactive with the game, but is really living in it.

Thumbnail photo courtesy of Newgrounds